|

| Are you not entertained?! |

Regardless of public opinion, this film holds up. It receives my full endorsement, but that's not what I'm here to talk about today.

2004 was a weird time to live. Music was bad, and had been for about eight years. TV was on the cusp of a new golden age. Broadband internet was finally becoming widely available to the masses, ushering in the new concept of digital media. And movies were getting gritty.

This was post-9/11 America. It was a time when citizens were still afraid, still looking over their shoulders, still keeping their heads down. The Iraqi and Afghani wars were going full-steam ahead with no signs of slowing. Insurgencies kept popping up. Soldiers kept getting ambushed. Planes and boats were being shot at. It was a terrifying time to be alive. Please, oh please, just let us live another day, mister terrorist man.

|

| Reasonable solution. Shoot the fear. |

It was also the year Michael Moore became a box office draw. He had previous, moderate success with Roger & Me, and Bowling For Columbine, but they were still just documentaries. You had to go out of your way to see them. The average person wouldn't have bothered. Fahrenheit 9/11, however, was a wide release. In the Summer. At the multiplex. It won the Cannes Film Festival. It was the number one movie in America at one point. This was no coincidence.

A subsection of Americans got tired of the constant paranoia in 2004. They were just done. I was a white suburban male high schooler, so of course I was on that liberal bandwagon, just as all angry, young 17 year-olds are to do. I'm neither pointing fingers or excusing my actions. We were all scared, and angry, and irrational back in 2004, and we all coped in our own ways. Some made radical, overly-simplified political statements, and some just tried their best to cope with the nonsense our world had become.

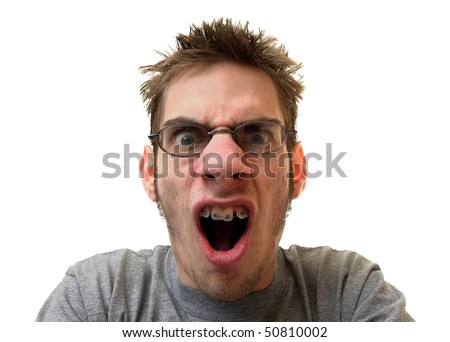

|

| Semi-accurate portrait of the writer as a young man. |

But what does any of this have to do with The Terminal? Back in 2004, Tom Hanks' character of Viktor Navorski was a mystery. He came from some non-descript, tumultuous, eastern-European nation called "Krakozhia," a stand-in for any soviet bloc nation. Due to language barriers and other such confusions, we don't know much about Viktor. He came from a war-torn homeland, he suffered from isolation, hunger, poverty, and due to a catch-22 in travel laws, he was forbidden from leaving the New York City airport.

The largest mystery is an omnipresent tin of Planters peanuts Viktor carries with him. Viktor's struggles with hunger plays a large, comedic role in the film's first act. Factoring in the age and dilapidated state of the can, it's strongly implied the tin no longer contains nuts. So what is inside?

The 2004-era mind races furiously. A bomb, or some sort of incendiary device? Chemical warfare? Nuclear waste, ready to serve? Retribution against American troops and figureheads? It all seems so insane that Tom Hanks, the nicest guy in Hollywood, could be a merchant of evil, but that was 2004 America's thought process. The voice of Woody the Cowboy could have been a sadistic madman.

|

| Seems legit. |

I watched the film again recently. If it hadn't been my own thought process, I'd never had believed anybody could have mustered such a ridiculously inept analysis of the film. Viktor Navorski is a clown. He's a happy-go-lucky guy caught in a bad situation. He makes the most of it. It's a testament to the indomitable human spirit against unfair odds. He has zero grudges towards anyone. He just wants to live. It's a far more innocent mystery today.

Films are a product of their eras, but also a product of all subsequent eras. It's amazing to see how a film can change, evolve, and dither based on shifts in public perception. More than that, how a film with no ill-intentions can trigger feelings and emotions based on personal identity. It just goes to show, sometimes something small and unassuming can reflect something grandiose.

No comments:

Post a Comment